abnormal psychology Notes

Module 4.1: Normality versus abnormality

What will you learn in this section?

- Approaches to defining abnormality

- Abnormality as a deviation from social norms

- Abnormality as inadequate functioning: Rosenhan and Seligman (1989)

- Abnormality as a deviation from ideal mental health: Jahoda (1958)

- The medical model of abnormality

Abnormality as a deviation from social norms

- In a very general and intuitive way we usually define abnormality as something that falls outside the boundaries of what is accepted in society. In other words, abnormality is a deviation from social norms.

- First, if abnormality is defined in relation to a society, how do we account for the fact that societies themselves are

different and changeable? Norms and rules regulating people’s behaviour are different from culture to culture. Even within the same culture, what was considered normal 100 years ago may be considered abnormal now, and vice versa. - Second, the fact that society gets to decide what behaviours are acceptable opens the door to using abnormality as a means of social control. If individuals do not behave in a way that serves a group’s interests, the group can label those people as abnormal and lock them out. This extreme position has given rise to a whole movement of “anti-psychiatry”. Thomas Szasz, one of the famous anti-psychiatrists, believed that “mental disorders” are nothing more than “problems in living”, a temporary inability to find one’s place within a given society. He believed that there is nothing wrong with individuals labeled “mentally ill” apart from the label itself.

- Third, some patterns of behaviour may be socially acceptable, but potentially harmful to the individual. For example, one could claim that there is nothing unacceptable about a person who is afraid to walk out of his house. However, the inability to leave the house due to irrational fears may interfere greatly with that person’s life.

- Finally, the abnormality must be evaluated in context. For instance, your behavior at a party and in school would be completely different, but they would both be acceptable in the given setting.

Abnormality as inadequate functioning: Rosenhan and Seligman (1989)

- The concepts of Rosenhan and Seligman (1989), who proposed seven criteria that can be used to determine abnormality, serve as the foundation for the definition of abnormality as deficient functioning.

a) suffering—subjective experience of one’s state as wrong

b) maladaptiveness—inability to achieve major life goals, for example, inability to establish positive interpersonal relationships

c) unconventional behaviour—behaviour that stands out and differs substantially from that of most people

d) unpredictability/loss of control—lack of consistency in actions

e) irrationality—others are unable to comprehend why the person behaves in this manner observer discomfort—it makes other people uncomfortable to witness this behavior

f) violation of moral standards—behaviour goes against the common moral norms established in the society. - A limitation of this approach is that it does not account for cases when abnormal behavior may actually be adaptive. For example, irrational fear that prevents a woman from leaving her house may serve the purpose of failure avoidance.

- Moreover, some behaviours may be destructive however we don’t rule them out as abnormal, for example, extreme sports. Some behaviors may be uncomfortable to the viewers,, but do not cause them any kind of particular suffering, for example, public displays of affection. Probably to account for this, Rosenhan and Seligman have agreed that the exist degrees of an abnormality based on how many criteria of abnormal behaviour is met.

Abnormalities as Deviation from Ideal Mental Health: Strawberry (1958)

- Humanistic psychologists proposed ideal mental health as a normality criterion in the 1950s. Humanistic psychologists were well-known for their belief that psychology ought to concentrate on the positive aspects of the human experience, such as health, happiness, and self-actualization, among other things. rather than things that are bad, like mental illness.

- They claimed that the excessive focus on the negative side of human existence predominant at that time was limited and did not allow researchers to see bigger issues lying behind problems, hence their interest in the idea of mental health (as opposed to mental disorders).

- In 1958, Marie Jahoda identified six indicators of ideal mental health:

a) efficient self-perception

b) realistic self-esteem

c) voluntary control of behaviour

d) accurate perception of the world

e) positive relationships

f) self-direction and productivity. - The fact that mental health is positively defined by one’s goals is a strength of this strategy. It likewise frames the primary elements of psychological well-being in a decent manner: It includes things like interpersonal relationships, self-perception, global perception, and so on.

- A weakness of this approach is the feasibility of mental health: it may be impossible to fully achieve all six parameters of mental health, so most people would probably be classified as abnormal under this framework. Another weakness is the fact that the parameters are difficult to measure or quantify. Finally, terms such as “effective”, “realistic” and “accurate” require further operationalization

The medical model of abnormality

- An alternative approach, rather than trying to formulate a common definition to fit all the possible types of mental disorders, is to look at each disorder separately and establish the number of symptoms that define it.

- Defining each disorder on the basis of its symptoms is known as the medical model of abnormality. This model assumes that disorders have a cause, but since the cause is not directly observable, it can only be inferred on the basis of more observable symptoms. For this reason, a medical classification of abnormal behaviour shows recognizable patterns of behaviour in each and every disorder

- A strength of the medical model is its flexibility. It allows for different perspectives on mental illness because it allows you to diagnose an illness regardless of your views on its causes.For instance, one doctor might think that depression is brought on by a chemical imbalance in the brain, while another doctor might think that depression is brought on by factors in the environment that cause too much stress. In any case, an identifiable set of symptoms allows them to reach a consensus about the presence of depression, that is, the medical model theoretically allows the diagnosis to be independent of the doctor’s theoretical orientation.

The fact that mental illness is much more difficult to apply to than physical disease is a major limitation of the medical model. Mental illness symptoms are harder to spot than physical symptoms. The necessity of determining which symptoms are associated with which disorders presents another issue when applying the medical model to abnormal behavior. Only a combination of symptoms can distinguish between disorders, and a single symptom can be an indicator of multiple disorders.

Module 4.2: Classification systems

What will you learn in this section?

- The history of DSM:

- DSM-I

- DSM-II

- DSM-III

- DSM-IV

- DSM-5

- Other classification systems: ICD-10, CCMD-3

The history of DSM:

1.) DSM-I

- DSM-I was published by the American Psychiatric Association in 1952 and included several categories of “personality disturbance”. For example, homosexuality was listed as a mental disorder. It remained in the DSM until 1974.

- DSM-I was heavily grounded in psychoanalytic traditions. This caused clinicians to look for origins of abnormal behaviour in childhood traumas. Homosexuality, for example, was explained by the fear of the opposite gender caused by relationships that caused trauma with the parents.

2.) DSM-II

- DSM-II was published in 1968. It was the result of a strong attack on both the psychiatric practices and the concept of mental illness itself.

- First, behaviourists criticized the use of unobservable constructs such as “trauma” or “motivation”.

- Second, the anti-psychiatry movement emerged, with figures such as Thomas Szasz pointing out that psychiatry may well be just another way to label non-conformists and establish social control.

- However, change does not happen rapidly. DSM-II was quite similar to DSM-I. It largely retained its psychoanalytical orientation. It was exploratory rather than descriptive, referring to possible origins of disorders. At first homosexuality was retained as a disorder, but under the pressure of gay rights activists it was removed from DSM-II in one of its reprints

3.) DSM-III

- DSM-III was published in 1980. In five groups (axes- the axial system) around 265 diagnostic categories were listed. This new edition was a response to increasing criticism from some scholars such as David Rosenhan. Doubts had been raised about various aspects of diagnosing mental illness. In a number of cases psychiatrists had been shown to be unable to discriminate between mental health and mental illness; some studies had attacked consistency of diagnosis; and some studies had questioned cross-cultural applicability of the DSM. The main shift was away from psychoanalytic interpretations and toward describing disorders rather than explaining them. The thought was that zeroing in on a portrayal and set of detectable side effects would increment understanding between specialists — less translation would be required, so there would be less subjectivity. One criticism that followed was the over-medicalization of the population: too many people met the criteria for mental illness.

4.) DSM-IV

- DSM-IV was published in 1994. It was the result of a very substantial revision process; a lot of experts were invited, split into groups, and each group conducted an extensive literature review, requested data from researchers and consulted clinical practitioners. The main shift was away from psychoanalytic interpretations and toward describing disorders rather than explaining them.

- The thought was that zeroing in on a portrayal and set of detectable side effects would increment understanding between specialists — less translation would be required, so there would be less subjectivity.

a) Clinical disorders. This axis included patterns of behaviour that impair functioning. Examples include schizophrenia or depression.

b) Personality disorders. These include rigid patterns of maladaptive behavior (which have become part of a

c) person’s personality. Examples include antisocial, paranoid or narcissistic disorders.

d) General health conditions.

e) Psychosocial and environmental problems contributing to the disorder, such as job loss, divorce, death of a close relative.

f) Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) on a scale of 1 to 100. This scale was to be used by the clinician to assess the current need for treatment.

Together these five axes were meant to provide a broad range of information about the patient’s mental state, not just

a diagnosis (Nevid, Rathus and Greene, 2014).

5.) DSM-5

- DSM-5 was published in 2013. The Roman numeral in the title was changed to Arabic as the plan was to update the DSM more frequently in future, with future editions reflecting both minor changes (using 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and so on) and major changes (6, 7, 8). A major change in the DSM-5 was that the multi-axial system was eliminated. This was a response to critics who said that the axial distinctions were not real and that in several more cases the same kind of disorders were artificially brought apart. We will return to DSM-5 diagnoses later in this unit when we consider diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Problems with artificiality of axial distinctions will be discussed in more detail in the context of validity and reliability of diagnosis.

Other classification systems: ICD-10, CCMD-3

- The World Health Organization formerly known as WHO maintains The International Classification of Diseases (ICd) This classification system is for all diseases including medical; behavioural abnormality is only part of it. It is in its tenth edition—ICD-10. ICD-10 is more widely used in European countries, while the DSM is in wider use in the USA.

- China uses a system called the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, currently in its third edition (CCMD-3). It is intentionally similar to the DSM and the ICD, both in terms of its structure and its diagnostic categories. However, some diagnoses are modified to better reflect the cultural realities. Also it includes around 40 unique culturally related diagnoses.

Module 4.3: Depression

What will you learn in this section?

- Description of Depression

- Explanation of a disorder

- Biological explanations of Depression

- Gene-environment interaction (GxE)

- The role of Neurotransmitters

- Cognitive Explanation of Depression

- Sociocultural Explantion of Depression

- Biological explanations of Depression

- Treatment of Depression

- Antidepressants

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Description of Depression

- DSM-5 formulates nine groups of symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDd) :

a) depressed mood

b) diminished interest or pleasure in daily activities

c) significant weight change, either loss or gain (more that 5% of body mass in a month)

d) insomnia or hypersomnia

e)psychomotor agitation or retardation (movement activity too fast or too slow)

f)fatigue

g)feelings of worthlessness or guilt

h)diminished ability to think or concentrate

i)recurrent suicidal thoughts

Explanation of a disorder

- Explanation of a disorder requires knowledge of its etiology—a set of causes of a disease or condition. Depending on our approach to understanding behaviour, we may distinguish between biological, cognitive and sociocultural etiologies of a disorder. Using the example of MDD, we will look at the existing explanations.

Biological explanations of Depression

- Biological explanations for depression embrace neurochemical factors (neurotransmitters and hormones) and genetic predisposition. Of course, these explanations are connected because abnormal levels of neurochemicals may be

determined by a person’s genetic set-up.

a) Gene-environment interaction (GxE)

- Gene-environment interaction (GxE) occurs when two different genotypes respond to the same environment in different ways. The trajectories of depressive symptoms among boys and girls from childhood to adolescence were studied by Silberg et al. (1999) in order to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to the distinct heritability of depression in males and females. Pre-adolescent boys and girls have similar rates of depression, according to previous research, but by middle-adolescence and beyond, girls’ prevalence of depression is well-established.

- The authors investigated the link between susceptibility to depression and environmental factors (stressful life events). They used data from more than 1,400 pairs of juvenile male-female twins who were followed longitudinally from ages 8 to 16. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Interview was used to measure depressive symptoms, and mother interviews were used to get ratings of life events over the past year. A failing grade or the death of a close friend as a result of arguments were among the list of life events that could cause stress.

- The longitudinal analysis revealed that negative life events had a greater impact on depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. This suggests that girls this age are more susceptible to stressful or negative life events because of their genetic predisposition. To put it another way, women revealed a “genetic predisposition to experience certain stressful life events” (Silberg et al., 1999, p. 230).

- This is an example of one way genes can interact with the environment: environmental factors serve as necessary mediators or triggers of genetic predisposition.

Molecular genetics

- Molecular genetics is also promising in this field of research because it allows us to identify specific genes influencing complex psychological disorders, whereas in twin, family and adoption studies where genes are not “measured” directly we can only talk about some broad, latent, unspecified genetic predisposition.

- Caspi et al (2003) found that a functional polymorphism in a serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT) moderated the influence of stressful life events on depression. This gene is involved in the reuptake of serotonin at brain synapses. In

This study a representative birth cohort of more than 1,000 children from New Zealand were followed longitudinally. The sample was divided into three groups:

a) both short alleles of 5-HTT

b) one short allele and one long allele

c) both long alleles. - Stressful life events that occurred after their 21st birthday and before their 26th birthday were assessed using a “biographical calendar” that focused on 14 major stressful events in areas such as work, finances, housing, health and relationships.There were no differences between the three groups in the number of stressful life events they experienced; however, individuals who had the short allele of 5-HTT exhibited more depressive symptoms in relation to stressful life events.

- More specifically, individuals who carried a short allele whose life events occurred after their 21st birthday experienced increases in their depressive symptoms from the age of 21 to 26 years, whereas individuals carrying the long/long alleles did not (even though they experienced the same events at the same time). Among participants suffering four or more stressful events of life, 33% of the individuals with a short allele of 5-HTT developed depression, compared to 17% of those having the long/long variant.

- Therefore, just as in Silberg et al, the study demonstrated that genetic set-up can moderate a person’s sensitivity to adverse environmental effects (life stress). However, this study allowed researchers to pinpoint the specific alleles responsible for this increased vulnerability to stressful events.

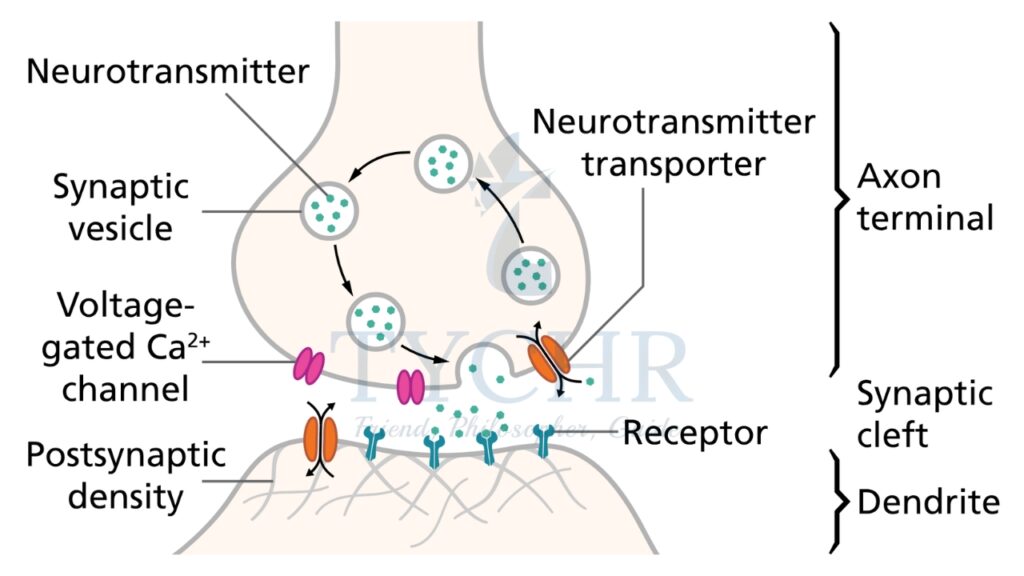

Gene-environment correlation

- The genes and environment are not completely independent—in many instances genes influence the environment too. So we need to look at how the interaction between these two factors is developing dynamically. This phenomenon is known as “gene-environment correlation”, and there are three ways in which genes may influence the environment

(Plomin, DeFries and Loehlin, 1977; Dick, 2011).

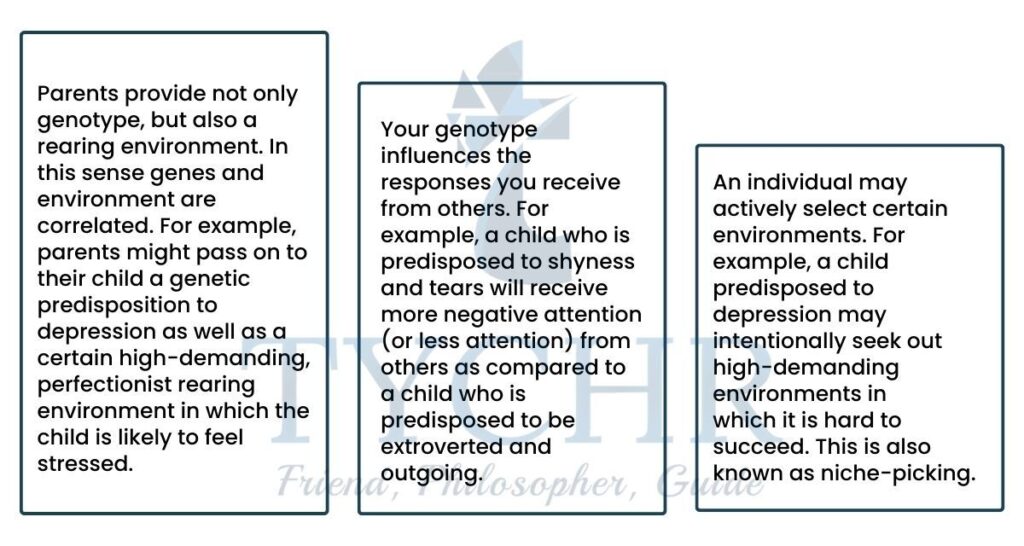

b) The role of Neurotransmitters

- The important point here is that sometimes what we think to be environmental influence actually has a genetic component in it. This genetic component only becomes evident if we look at gene-environment interaction dynamically. As a matter of fact, serotonin has been the most widely discussed neurotransmitter in the context of depression studies. The clinical depression’s “serotonin hypothesis” is about 50 years old. This hypothesis states that

Low levels of serotonin in the brain play a causal role in developing MDD. Mostly this hypothesis has been based on two types of finding.

a) Certain drugs (prescribed for completely different purposes) that were known to deplete levels of serotonin in the brain were also found to have depression-inducing side effects.

b) Certain drugs such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAO inhibitors) were found to be effective against symptoms of depression. Such findings were mostly due to chance, but later in carefully controlled animal studies MAO inhibitors were also shown to enhance effects of serotonin at the synapse (Cowen and Browning, 2015).

c) Another class of drugs that was discovered later is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). As the name suggests, these chemicals inhibit the reuptake of excess serotonin in the synapse, increasing synaptic concentration of serotonin. SSRIs were also shown to be effective against symptoms of depression. - You might think that this pattern of findings is convincing evidence of the causal effect of serotonin in depression, but it’s not that simple. Essentially, the findings are based on what is known as “treatment etiology fallacy”: treatment X (which targets chemical Y) reduces symptoms of depression, therefore, chemical Y causes depression. This might not be entirely true for several reasons.

Cognitive Explanation of Depression

- Aaron Beck’s (1967) cognitive theory of depression is perhaps the most influential and empirically supported explanation of depression that views cognitive factors (thoughts and beliefs) as the major cause of depressive behaviour. Beck noticed the importance of so-called “automatic thoughts”—sub-vocal semi-conscious narrative that accompanies everything you do.

- For many researchers those automatic thoughts were a by-product of other phenomena (behaviour, attitudes, and so on), but Beck saw a causal relationship and suggested that a change in automatic thoughts can lead to a change in behaviour. He noticed that automatic thoughts of patients with depression were often dark, exaggerated and irrational, for example, a person would automatically think, “Here we go again, I am such a loser” after every minor setback. So, cognitive theory of depression concentrates on the negative appraisal of events.

- Beck’s cognitive theory identifies three elements of depression.

1) The cognitive triad. It includes deeply grounded beliefs about three aspects of reality

a) the self (“I am worthless”, “I wish I wasn’t the way I am”)

b) the world (“no one notices me”, “people do not take me seriously”)

c) the future (“things can only get worse”, “my efforts will be fruitless”).

2) Negative self-schemas. Beck suggested that negative self-schemas may be the result of traumatic childhood experiences such as excessive criticism, family abuse, or bullying.

3) Faulty thought patterns. The above negative beliefs lead to a number of cognitive biases that people with depression often resort to when interpreting their everyday experiences. Some of the faulty thinking patterns common to depression are:

a) arbitrary inference (drawing far-fetched conclusions from insufficient evidence)

b) selective abstraction (noticing one aspect of experience and ignoring others

c) overgeneralization (making conclusions on the basis of a single event)

d) personalization (blaming oneself for everything)

e) dichotomous thinking (black-and-white attitudes, “I am either a success or a total failure”). - Cognitive explanations for depression have many strengths, including strong empirical support and the fact that patients in cognitive behavioral therapy are to be seen as individuals who take responsibility for their own problems and have the ability to solve them on their own. Many successful therapies are built on the cognitive approach

- Some criticisms of these explanations have focused on the correlational nature of most research studies. It is difficult to distinguish between thinking that causes depression and thinking that is caused by depression. For example, in the study of Alloy, Abramson and Francis (1999) the negative thinking style of one group of participants might have been determined by their predisposition to depression in the first place.

Sociocultural Explanation of Depression

- Brown and Harris (1978) proposed a model of depression which outlines how “vulnerability factors” may interact with triggering stressors to increase the risk of depression. They reported results of a community study of 458 women from London who were surveyed on the history of life events and depressive episodes. Semistructured interviews were used to gather in-depth information.

- The study demonstrated that it is not only personal factors that are involved in the development of depression, but social factors as well. In particular, Patten (1991) summarized the quantitative results of replications and concluded that the lack of an intimate relationship increases the risk of developing depression 3. 7 times, whereas each of the The other three factors “only” double the risk. According to Patten (1991), this risk increase is comparable, for instance, to smoking as an atherosclerosis risk factor.

- Rosenquist, Fowler, and Christakis (2011) examined the possibility of person-to-person transmission of depressive symptoms. Of course, simply showing that people who are friends are more likely to experience depression together would not be enough. Such a result could be explained in at least three ways.

1) Depression in one person causes depression in his friends.

2) Depressed individuals notice each other and become friends.

3) The friends experience similar social and economic environments, which explains their similar symptoms. - Interestingly, directionality of friendship also appeared to be important. For example, in a couple where A nominated B as a friend but not vice versa (A → b) , if B becomes depressed it doubles the chances of A also becoming depressed in the near future. If A becomes depressed, it has no effect on B. In contrast, in a mutual friendship (A ← → b) , when B becomes depressed it increases the chances of A becoming depressed by 359%. This result suggests that explanation

(1) should be preferred to explanation (3). - Lastly, cultural perceptions, such as cultural stigma, play a significant role in the onset and presentation of depressive symptoms.

Treatment of Depression

1) Antidepressants

Biological treatment of depression is based on the assumption of chemical imbalances in the brain as the major factor of the development of depression. This leads to the idea that if we restore the balance of neurotransmitters in the brain, depression symptoms will be reduced. The class of drugs that target key neurotransmitters involved in depression is known as antidepressants.

a) Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were named this because their chemical structure contains three rings of atoms.

- The mechanism of the action of these drugs is the inhibition of reuptake of certain neurotransmitters (such as serotonin and norepinephrine) after they have been released in the synaptic gap. This increases the concentration of neurotransmitters available in the synaptic gap.

- TCAs were shown to be effective, but later on they were largely replaced by other drugs because their side effects were sometimes quite severe (they included weight gain and dizziness, and an overdose could be fatal).

b) MAO (monoamine oxidase)

- MAO (monoamine oxidase) inhibitors are another well-known class of antidepressants. Monoamine oxidase is a chemical that breaks down monoamine neurotransmitters (such as serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine). So, inhibiting monoamine oxidase leads, again, to an increase in the concentration of monoamines in the brain.

- This class of drugs has been shown to be particularly effective in treating atypical depression. However, some serious side effects were also reported.

c) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), probably the most widely used class of antidepressants, function, as their

name suggests, by selectively inhibiting reuptake of serotonin. This is the best thing about them—they block reuptake of serotonin only, not anything else. - This means the number of potential side effects is smaller. In a sense, they are also “better” for scientific research— since we are only manipulating one independent variable (serotonin), it is easier to clearly attribute the observed reduction of symptoms to a certain cause.

2) Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- CBT is based on the assumption that the underlying cause of depression is maladaptive automatic thoughts that lead to irrational behaviour. irrational behaviour. As the name suggests, CBT targets both the automatic thoughts, to replace them with more reality-congruent information processing, and the behaviour, in an attempt to make it more rational and adjusted to the environment.

- There are several features of CBT that make it different from many other forms of therapy.

a) It has two major goals: cognitive restructuring and behavioural activation (change the way you think and start acting accordingly).

b) It focuses on specific, well-defined problems.

c) Patients are expected to be active, for example, they are given home assignments that are subsequently discussed or even graded. - Specific techniques used in a regular CBT session include the following.

Socratic Questioning

- Essentially, the therapist uses a series of questions that gradually lead the client to the realization that their beliefs are not rational nor are they supported by evidence. For example, the therapist might ask: “You claim that your colleagues think that you are useless. Name all the things that happened yesterday that support this claim.”

Behavioural Experiments

- This technique is designed to counteract maladaptive beliefs. For example, On particular days she would have to speak and participate in class and register her feelings and thoughts, much like scientists do when they observe their participants. On other days she would have to be reserved, sit at the back of the class and answer vaguely and superficially.

Thought Records

- This technique is also designed to challenge dysfunctional, irrational or unrealistic automatic thoughts. The client and the therapist identify a belief they want to explore and the client receives the assignment to keep systematic records of both the thoughts and the situations relevant to this belief. For example,If the client feels she is being disrespected by colleagues at work, she may be asked to keep a record of all relevant situations, for example, someone at work asked her for advice, someone offered her help, someone initiated a conversation. Looking at this systematically collected evidence, the client begins to realize that she has been ignoring evidence contradicting her dysfunctional belief.

Situation Exposure Hierarchies

- In this technique the client makes a list of what she herself is in the most stressful environment or behaviours. For example, examinations may be very stressful for a depressed patient (because it involves a potential threat to already low self- esteem). The client makes a list of examination-related scenarios and arranges them on a continuum from 1 (least stressful, such as playing chess with a friend) to 10 (most stressful, such as taking a course online and having a high- stakes examination at the end of the course). After that the client is encouraged to try out behaviours from the bottom of the list until they become less stressful, and in this manner gradually makes her progress closer to the top of the list.

Pleasant Activity Scheduling

- The client agrees (as part of her homework) that she will do one pleasant activity every day— something that she does not normally do, but something that brings her positive emotions or a sense of competence or mastery. This could be something very simple and quick like practising playing the guitar for 10 minutes or going outside to read a short chapter in a detective book.

Module 4.4: OCD

What will you learn in this section?

- Description of OCD

- Explanation of a disorder

- Biological explanations of Depression

- Genetic explanation

- Neural explanation

- Evolutionary explanation

- Psychological explanations

- Behaviourist explanation

- Cognitive Explanation

- Psychodynamic explanation

- Biological explanations of Depression

- Treatment of Depression

- Biological Treatment

- Psychological treatments of OCD

Description of OCD

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder {OCD} is an anxiety related mental disorder. As with all anxiety disorders, OCD is characterized by Fear reactions that are so high they become maladaptive, negatively affecting suici’erers1 ability to function eFFectively in everyday life, with 2 percent of the population suffering from OCD.

- OCD is an exaggerated version of normal behaviour and is perceived as a mental disorder when an individual’s behaviour becomes detrimental to everyday functioning. For instance, when a sufferer’s obsession with contamination means they cannot perform any meaningful work.

Obsessions

- Obsessions consist of forbidden or inappropriate ideas and visual images, leading to feelings of extreme anxiety.

a) Common obsessions include:

b) Contamination, eg. by germs

c) lack of control, e.g. through intentions to hurt others

d) Perfectionism, e.g. fear of losing important things

e)Unwanted sexual thoughts, e.g. fear of being homosexual

f)Religion, e.g. fear of being immoral.

Compulsions

- Compulsions consist of intense, uncontrollable urges to repetitively perform tasks and anti behaviours. such as constantly cleaning door handles. Compulsive behaviours serve to counteract, neutralize or make obsessions go away, and although OCD sufferers realize that compulsions are only a temporary solution. they have no other way to cope so rely on their compulsive behaviours as a short-term escape. Compulsions can also include avoiding situations that trigger obsessive ideas or images. Compulsive behaviours are time-consuming and get in the way of meaningful events, such as work and conducting personal relationships. Behaviours are only compulsive in certain contexts. For example, arranging anti-ordering books is not compulsive if the person is a librarian.

- Common compulsions involve:

a) Excessive washing and cleaning, cg. teeth-brushing

b) Excessive checking. e.g. doors are locked

c) Repetition, e.g. of body movements

d) Mental commissions, e.g. praying in order to prevent harm

e)Hoarding, e.g. of magazines.

Explanation of the disorder

1) Biological explanations

- Biological explanations see OCD as arising from physiological factors. Three possible biological explanations are:-

a) hereditary influences through genetic transmission

b) the occurrence of OCD through damage to neural {brain} mechanisms and

c) that OCD has an evolutionary adaptive survival value that has been acted upon by natural selection.

a) Genetic explanation

- The genetic explanation here centers on OCD being inherited through genetic transmission, with research initially focusing on twin and family studies to assess whether this view is valid and, if so, to what extent genes play a role. However, as in other areas of psychology, the problem with twin studies is disentangling the relative influences of genes and environment.

- With the introduction of DNA profiling, recent attention has focused on gene mapping studies, which involve comparing genetic material from sufferers and non-sufferers. Such studies also allow researchers to determine whether OCD is truly a separate disorder, as OCD sufferers often also have Tourette syndrome.

- The results of both forms of study suggest a genetic link to OCD, with specific genes involved that make some individuals more susceptible to developing the disorder than others.

- It is unlikely that any single gene causes OCD: it is more likely that it is a combination of genes that determine an individual’s level of vulnerability to the condition.

b) Neural explanation

- Some forms of OCD have been linked to breakdowns in immune system functioning, such as through contracting streptococcal (throat) infections, Lymes disease and influenza, which would indicate a biological explanation through damage to neural mechanisms. Such onset of the disorder is more often seen in children than adults.

- PET (positron emission tomography) scans also show that OCD patients’ brains have relatively low levels of serotonin activity. Since drugs that increase serotonin activity have been found to alleviate OCD symptoms, this suggests that the neurotransmitter may be involved in the disorder.

- PET scans also show that 0CD sufferers can have relatively high levels of activity in the orbital-frontal cortex, a brain area associated with higher-level thought processes and the conversion of sensory information into thoughts. The brain area is thought to help initiate activity upon receiving impulses to do so and then to stop the activity when the impulse lessens.

- A non-sufferer may have an impulse to wash dirt from their hands; once this is done the impulse to perform the activity stops and thus so does the hehaviour. It may be that those with OCD have difficulty in switching off or ignoring impulses1 so that they turn into obsessions, resulting in compulsive behaviour.

c) Evolutionary explanation

- Historical evidence indicates that OCD has been around for a long time. The fact that it continues to be apparent in the population suggests that OCD has an adaptive value and therefore an evolutionary basis. So, rather than perceiving OCD in maladaptive terms, evolution views the disorder as fulfilling a useful purpose. OCD involves repetitive behaviours like washing and grooming and these would have had an adaptive value in protecting against infection.

- The evolutionary explanation also includes the idea of biological preparedness, a concept suggested by Seligman (1971) that sees animals as possessing an innate ability to display certain anxieties as they possess an adaptive value linked to survival and reproduction abilities. Thus we may develop some conditioned anxieties easier than others. For example, a fear of infection, as this would have constituted a serious threat in the Pleistocene era (when most evolution occurred. Such anxieties have genetic and environmental components, as anxieties have to he learned from environmental experience, with the predisposition to learn the anxiety being the inherited component. it would be much harder to develop an anxiety about being shot, as a risk of being shot did not exist in the Pleistocene era.

2) Psychological explanations

- Psychological explanations see OCD as arising from non-physiological factors. Three possible psychological explanations for OCD are:

a) the behaviourist explanation which sees OCD as a learned condition through reference to classical and operant conditioning and social learning;

b) the cognitive explanation which sees OCD as being caused through irrational thought processes

c) the psychodynamic explanation, which sees OCD as linked to the anal stage of psychosexual development.

a) The behaviourist explanation

- The behaviourist explanation sees OCD as being a learned condition, through the application of classical

1. conditioning (Cc)

2. operant conditioning (Dc)

3. social learning theory (BLT). - The acquisition of OCT) is seen as occurring through CC, where a neutral stimulus becomes associated with threatening thoughts or experiences and this leads to the development of anxiety. For example, the neutral stimulus of shaking hands with people becomes associated with thoughts of becoming contaminated with germs by doing so (or through the experience of actually being contaminated in this way). This can also occur through SLT1 where an individual sees or hears about this event occurring to someone else and then imitates it.

b) The cognitive explanation

- The cognitive viewpoint sees some people as being more vulnerable to developing OCD because of an attentional bias, where perception is focused more on anxiety-generating stimuli. OCD sufferers also have faulty, persistent thought processes that focus on anxiety-generating stimuli, such as estimating the risk of infection from shaking hands to be much higher than it actually is.

- 0CD sufferers, on the other hand, tend to have maladaptive thoughts and beliefs about stimuli. Because they reduce anxiety, behaviors that lessen impaired obsessive thoughts become compulsions.

- The cognitive explanation also sees compulsive behaviours as being due to cognitive errors, based on sufferers having a heightened sense of personal responsibility, which motivates them to carry out compulsive behaviors to avoid negative outcomes. This has a behaviorist element, where compulsive behaviors are seen to be reinforcing by reducing anxiety.

- However, the demonstration of compulsive behaviors means sufferers do not get to test out their faulty thinking and realize that actually there will not be a negative consequence if they do not demonstrate compulsive behaviors.

c) The psychodynamic explanation

- The psychodynamic explanation of OCD sees the ego (the conscious, rational part of personality) as being disturbed by obsessions and compulsions, which leads to sufferers using ego defense mechanisms {unconscious strategies that reduce anxiety), such as:

- isolation, where the ego of a sufferer separates itself from the anxiety produced by unacceptable urges of the id (the irrational, pleasure seeking part of personality) by perceiving such urges as not belonging to them. However, such urges intrude as obsessive thoughts.

- Undoing, where the anxiety produced by undesirable urges can be addressed by performing certain compulsive behaviors [such as reducing fears of contamination by h&r washing.

- Reaction formation, where the anxiety produced by undesirable urges is addressed by adopting behaviors that are the opposite of the undesirable urges (like becoming celibate to cope with obsessive sexual impulses).

Diathesis-stress explanation

- Rather than viewing OCD as resulting from any single explanation. It may be more sensible to regard the disorder as due to a combination of explanations that include both nature and nurture elements. For instance, it could be that certain personality types that result from genetic influences (through effects upon neural functioning) are more vulnerable to developing the disorder through environmental learning influence.

- The irrational thinking associated with the disorder that is the central feature of the cognitive explanation could also be seen as under genetic influence. which is itself transmitted through evolutionary means. A diathesis stress explanation could account for individual differences, such as where one identical {ME} twin develops the disorder and the other does not. Both twins would have an equal genetic vulnerability to developing OCD, but only one does due to having different environmental learning experiences.

Treatment of OCD

1)Biological Treatment

a) Drug therapy

- OCD is treated with antidepressants like SSRIs, which raise serotonin levels and restore normal function to the orbital cortex. The most common SSRI use with adults is fluoxetine (Prozac) . For children aged six years. Sertraline is usually prescribed and fluvoxamine for children aged eight vents and older. Treatment usually lasts for 12-16 weeks.

- Anxiolytics drugs are also used due to their anxiety-lowering properties. Antipsychotic drugs that have a dopamine lowering effect have also proven useful in treating OCD, though are only generally given after treatment with SSRls has not proved to be effective (or incurs serious side effects).

- Betarblockers also reduce the physical symptoms of OCD. They work by countering the rise in blood pressure and heart rate often associated with anxiety, lav lowering adrenaline and noradrenaline production.

b) Psychosurgery and deep-brain stimulation

- Psychosurgery involves destroying brain tissue to disrupt the corticostriatal circuit by the use of radio frequency waves. This has an effect on the orbital-frontal cortex. The thalamus anti the caudate nucleus brain areas and is associated with a reduction in symptoms. There has been a recent movement towards using deeper stimulation, which involves the use of magnetic pulses on the supplementary motor area of the brain. which is associated with blocking our irrelevant thoughts and obsessions.

2) Psychological treatments of OCD

a) Cognitive therapy

- CBT is a common treatment for OCD, treatments occurring once every 7-14 days for about 15 sessions in total, with CBT orientated at changing obsessional thinking, such as with habituation training (HT), where sufferers relive obsessional thoughts repeatedly to reduce the anxiety created. All types of maladaptive thoughts associated with can be successfully addressed with CBT; intrusive thoughts are shown to be normal and patients come to understand that thinking about a behavior is not the same as actually doing it. Suffererslearn to focus on estimates of potential risks and realistically assess the likelihood of them occurring. Sufferers are encouraged to practice new adaptive beliefs and to disregard their former maladaptive ones. Although CBT is seen as the most effective treatment for OCD, even higher success rates are found when it is combined with drug treatments.

- CBT can be given as an individual treatment, or as a group therapy, such as by group CBT (GCBT), where the basic aim, as with individual CRT, is to change obsessional thinking and develop new adaptive beliefs, but interaction with fellow OCD sufferers provides additional support and encouragement and decreases the feelings of isolation that can aggravate OCD symptoms.

- GCBT for OCD often incorporates exposure and response prevention (ERP) involving exposure to a feared obsession (either imagined or for real) until the fear subsides, and response prevention, where the usual ritual response is not allowed to occur.

b) Psychodynamic therapy

- Psychodynamic therapies contain biological, cognitive and sociocultural elements.

- Psychodynamic therapies have not been seen as an effective treatment for OCD indeed some clinicians have perceived them as more harmful than useful in alleviating symptoms. However there has been a recent move towards viewing

certain types of psychodynamic therapies are useful with certain types of patients especially after treatment with drugs and CBT has not reduced their symptoms. - Psychodynamic therapies may especially have a useful role to play with patients who have comorbid conditions, especially those additionally suffering from borderline personality disorder (BPd) and patients whose OCD developed in adulthood due to stressors based upon interpersonal relationships. as well as those whose 0CD may emanate from unresolved crises in childhood.

- Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy (DDP) is a form of psychodynamic therapy that has produced some promising results. The aims of DDP are to get patients to connect with their own emotional experiences, in order to gain a better sense of self, and to get them to connect with other people in more meaningful ways in order to develop better interpersonal relationships.

- The main focus is on social interactions with a therapist helping a patient to identify the emotions they experience in relation to their condition and getting them to explore other ways of interpreting their interactions with people. This serves the purpose of deconstructing attributions about oneself (how an individual regards themselves and their behavior) and replacing them with more positive attributions.

- DDP occurs as weekly sessions of 45 minutes for up to 12 months of treatment. Between sessions patients assess their emotional experiences by completing Daily Connection Sheets in order to buiId better social relationships outside of treatment. At the end of treatment. Some patients will require monthly maintenance sessions or six-month blocks of +booster sessions.

Module 4.5: Anorexia nervosa

What will you learn in this section?

- Description of Anorexia Nervosa

- Explanation of a disorder

- Biological explanations

- Genetic explanation

- Neural explanation

- Evolutionary explanation

- Psychological explanations

- family systems theory

- social learning theory,

- cognitive Explanation

- Biological explanations

- Treatment of Depression

- Biological Treatment

- Psychodynamic therapy

Description of Anorexia nervosa

- Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a mental disorder characterized bv three main criteria:

a) self-starvation,

b) strong motivation to lose weight through fear of being fat and

c) medical signs and symptoms that result from starvation. - AN has existed for a long time, but has become more widespread in recent years. AN can occur at different times of life and to differing degrees: 20 percent of sufferers recover after one episode, 60 per cent continue to have periodic episodes, while 20 per cent will be hospitalized for lengthy periods. About 15 per cent of sufferers will die from starvation/ suicide/electrolyte imbalances and organ failure. AN is believed to have the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. Brain damage and infertility can also occur.

Subtypes of AN

- Restricting type – a subtype where weight loss is achieved through dieting, fasting and/or excessive exercise. There are no regular episodes of binging or purging.

- Binge-eating/purging type – a subtype where there are regular episodes of binging and for purging. Self Induced vomiting and use of laxatives, diuretics and enemas to elicit purging.

Explanation of the Disorder

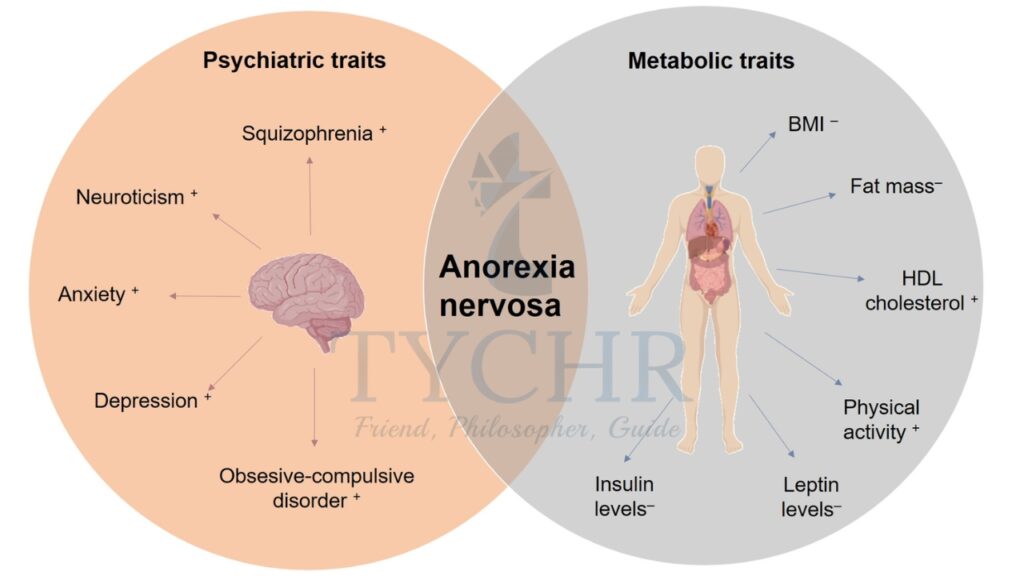

Biological explanations

- Biological explanations see AN as resulting front physiological factors. Three possible biological explanations are

a) the genetic explanation, which sees AN as an inherited condition,

b) neural explanations, which sees AN as linked to defective brain structures,

c) evolutionary explanations, which have an evolutionary adaptive survival value that has been acted upon by natural selection.

a) Genetic explanation

- The genetic explanation sees AN as transmitted through hereditary means from the genetic material passed from parents to children. Evidence indicates an increased risk for individuals with close relatives with the disorder, which suggests that the disorder is in part genetically transmitted.

- However, the genetic explanation is seen as only a contributory factor in the causation of the disorder. What genes may do is give individuals a level of inherited vulnerability- to developing the disorder, with different individuals having differing levels of vulnerability.

- Whether a given individual goes on to develop AN would depend upon the presence of other factors, for example levels of environmental stress, types of family structure, and so on.

b) Neural and biochemical explanations

- Neural explanations involve the idea that AN is linked to defective brain structures. Early research focused on possible damage to the hypothalamus, especially damage to the lateral hypothalamus, but more recent research has concentrated on identifying specific brain mechanisms. One area of interest is the insula dysfunction hypothesis as the biological root of anorexia.

- This sees the insula brain area, part of the cerebral cortex, as developing differently in anorexics. Various symptoms of AH are associated with dysfunction in several brain areas, with the common factor being the insula which is responsible for more neural connections than any other part of the brain, including brain areas associated with AN. Contemporary research appears to back up the hypothesis.

- Neural explanations also involve the idea that faulty biochemistry is related to the development of AN. The neurotransmitter serotonin is especially linked with the onset and maintenance of anorexia, though noradrenaline is also of interest with its role in maintaining restriction of eating by influencing anxiety levels.

- Leptin also attracts interest, as anorexics can have low levels of leptin, probably due to their low levels of fat, it is thought that leptin influences the regulation of the neuroendocrine system during starvation. Low leptin levels are also known to affect the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis, which leads to the amenorrhea (cessation of periods) often seen in anorexics.

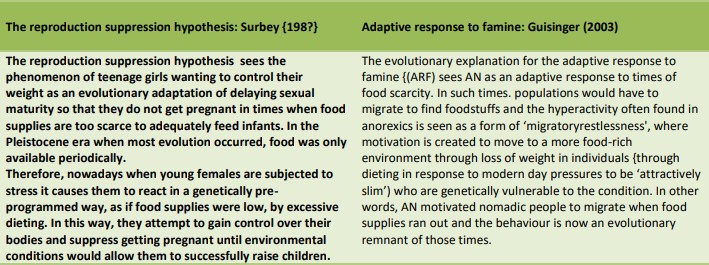

c) Evolutionary explanations

- Evolutionary explanations see AN as having an adaptive survival value that has been acted upon by natural selection. This explains why the disorder has existed throughout the ages and continues to be apparent in the population. If AN did not fulfill an adaptive purpose, then natural selection would have caused it to die out.

2) Psychological explanations for anorexia nervosa

- Psychological explanations see AN as arising from non-physiological factors. Three possible psychological explanations are:

a) family systems theory, which sees AM as arising from dysfunctional patterns of family interaction.

b) social learning theory, which sees AN as being a condition learned through the observation and imitation of role models

c) cognitive explanation, which sees AN as resulting from irrational thought processes.

a) Family systems theory

- The family systems theory (FST) sees families as deeply emotionally connected to each other with family members

seeking each other’s attention and approval and continually reacting to each other’s needs and moods. - Thus families are interdependent units, where change in the functioning of one member affects the functioning of other members. AN is seen as growing because of dysfunctional interactions between family members, with its development often serving to prevent or reduce dissension (disagreements) within a family.

- For example, an adolescent fearing that arguments between parents may lead to divorce becomes anorexic to divert family attention onto themselves, thus saving the marriage. In other words. the family is ‘sick’. but the anorexic

becomes the ‘fall guy’(takes the blame) for the family’s problems with the anorexic often fearing abandonment or

worsening of the family’s problems unless they accept their role.

b) Social learning theory

- Social learning theory (SLT) sees learning as occurring through social means, where someone is observed being rewarded for their behavior and that behavior is then imitated.

- The SLT of AN is based on the idea that people want to be popular and that mimicking the thinness of popular people will achieve this goal. Young people are considered particularly vulnerable as they search for identity and increased self-esteem.

i. Modeling

- Modeling is an important aspect of SLT, where learning involves extraction of information from observations and making decisions about the performance of the behavior. In this way, learning occurs without noticeable changes in behaviour. There are three types of modeling cues:

- A live model demonstrating the desired behavior (eg praising a thin person).

- Verbally instructing an individual about desired behavior.

- Symbolic modeling through media presentations of desirable behavior (e.g. photos of thin models in magazines).

- Effective modeling depends on:

- the amount of attention paid to the observed behavior,

- retaining a mental image of the observed behavior

- mental image reproduction

- they have an incentive to imitate the behavior.

ii. Reinforcement

- Another important part of SLT is amplification. When observed behavior is imitated, others respond; if the response is rewarding, it increases the chances that the behavior will occur again because the behavior has been reinforced (reinforced) .

- Empowerment can be external, such as gaining approval from others for losing weight, or internal, such as feeling better about oneself. Reinforcement can also be positive, such as receiving compliments for being thin, or negative, such as no longer being teased for being chubby.

iii. Media

- In SLT, the media is a powerful force. Extreme thinness is portrayed as desirable by models in women’s magazines in Western cultures. AN develops as a result of the observation and imitation of these images. This may help explain why women are more likely than men to be anorexic because women are exposed to media images of thinness that are more “desirable.”

- It also makes sense why women who move from societies in which such media images do not occur to societies in which they do become more powerless to prevent AN.

c) The cognitive explanation

- The cognitive explanation sees AN as causing he a hrealtt’it’iwn in rational thought processes, like an individual wishing to attain an unreal level of perfection in order to be an acceptable person. This level of perception is seen as attainable by developing an extremely thin body type.

i. Distortions

Distorted thought processes include errors in thinking that negatively affect the perception of body image. Because of these distortions, people adopt rigid, inflexible eating rules, and breaking these rules can result in feelings of guilt and failure, lower self-confidence, and self-doubt, which in turn can cause even more severe anorexia.

ii. Irrational beliefs

- Anorexics frequently misperceive their body image and believe they are fatter than they actually are as a result of irrational beliefs, which are maladaptive ideas that cause AN to develop and persist. Additionally, anorexics will have flawed eating habits.

Treatment of Anorexia nervosa

1)Biological Treatment

a) Drug therapy

- Drugs are generally not seen as an effective treatment for AN on their own but can have some effectiveness when combined with other psychological treatments. Antidepressant SSRls, such as Prozac and Sarafem are seen as useful in treating anorexics who have hemorrhoid anxiety disorders and for depression. with the antipsychotic drug olanzapine also sometimes used to reduce feelings of anxiety related to weight and dieting in patients who have not responded to other treatments.

- SSRIs only tend to be prescribed to patients who have started to put weight on, as the risk of side effects is heightened in people who are underweight. especially that of loss of appetite and further weight loss. Also, SSRls are generally only given to patients over the age of 13.

- When SSRI are prescribed, the patient will take them for some weeks before any improvement in symptoms is seen. As well as reducing feelings of depression in anorexics, SSRls can help patients to maintain a healthy weight once control over weight and eating has been established.

- SSRls increase serotonin levels. a neurotransmitter that affects mood. Olanzapine tends to be given if SSRls have had little beneficial effect and can help some sufferers to gain weight and reduce obsessive thinking. Drugs cannot cure anorexia but can help to control urges to binge or purge and excessive focus on food and dieting.

b) Other biological therapies

- Other biological therapies include:

1.) Mandometer – a device that gives patients feedback on their rate of eating, which can be used to accelerate the rate of eating in anorexics.

2.) Repetitive transcortical magnetic stimulation (rTMS) a treatment involving brain stimulation, usually used to treat depression and anxiety, whereby an electromagnetic coil is used to generate magnetic pulses to targeted brain areas. This induces an electrical current in specific nerve cells, which causes a stimulation that positively affects mood. Attempts are now being made to assess its effectiveness in treating AN, due to many sufferers having high levels of anxiety and comorbid conditions involving heightened levels of depression and anxiety.

2)Psychological treatments of OCD

a) Cognitive therapy

- Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT ) is a common method of treating AN. CBT stresses the role that maladaptive cognitions (thoughts) and behaviors piss in onset and maintenance of AH.

- Maladaptive cognitive factors include: preoccupation with weight and body shape, food and eating, negative body image, negative self-worth, negative self-evaluation and perfectionism.

- Maladaptive behavioral factors include: severe dieting ,purging, constant weighing, selfearn individuals who have negative, distorted perceptions of themselves and their bodies develop feelings of shame and disgust that trigger weight control behaviors and a repeating cycle of negative self-evaluation. CBT. delivered by a trained therapist. gets sufferers to identify the factors that help to maintain their anorexic behavior.

- The main emphasis is on teaching skills to patients to help them not only understand why they are anorexic, but also to help develop new, more adaptive ways of thinking and behaving in order to maintain a stable, healthy weight.

- CBT for AM occurs in three phases, which can be delivered to patients inside and outside of hospital:

i. Behavioral phase

therapist and patient work together to create a plan for stabilizing eating behavior and reducing anorexic symptoms. Coping strategies are taught and practiced that help the patient to deal with the intense negative emotions that can arise at this time.

ii. Cognitive phase

cognitive restructuring skills, which help patients to identify and alter negative thinking patterns, are taught. For example, identifying that can only he of worth if I lose weight1 is maladaptive, and is altered to my

Happiness doesn’t depend on my weight. Also at this stage, relationship, body image and self-worth problems are addressed, as well as methods of controlling one ‘s emotions.

iii. Maintenance and relapse prevention phase

focus is on reducing factors that trigger anorexic thoughts and behavior and developing strategies to prevent relapsing hack into an. After anorexic symptoms have been dealt with, the final focus is on other areas of concern and conflict that could precipitate such a relapse.

b) Psychodynamic therapy

- Psychodynamic therapy (PDT) focuses on symptoms as being related to disturbances in relationships. For example, a sufferer may be seen as fearful of greed, which manifests itself through limiting their food intake to appear less greedy with this perceived as being symbolic of similar patterns within a sufferer’s interpersonal relationships, where there are fears of having feelings of dependency on others.

- Anorexia generally see dependency as a sign of weakness and so they develop anorexic behaviors as a way of showing they are not dependent on food. With the focus now on controlling food and body weight, interpersonal relationships become less important and the anorexic creates a sense of being emotionally and physically self- sufficient.

- The role of a psychotherapist is to help the patient understand their unconscious thoughts. feelings and behavior so that such insight will help them to change and repair relationships with themselves and others.

i. Focal psychodynamic therapy is a form of PDT, which sees AN to be linked to unresolved conflicts that occurred in childhood, mainly during the oral stage of psychosexual development. By getting patients to assess how early childhood experiences may be linked to their anorexic behavior, it is seen as assisting them, with help from a therapist, to find effective ways of coping with stressors and negative thoughts and feelings.

ii. Interpersonal therapy (IT) is another form of PDT, which focuses on relationships with others and the external world as being linked to mental health. AN is seen as being related to perceptions of low self worth and high anxiety, caused by problems with interpersonal relationships. During treatment a therapist helps a patient to assess negative factors associated with interpersonal relationships and to form and practise strategies to resolve them.